What does the economic impact of the pandemic mean to the bottom line of major film studios? We examine the possibility of the reduction of the traditional box office and what that means for the way movies will be made in the future.

Of the top ten grossing films of 2019, all of them were sequels, spin offs, or remakes except for one (Joker, which might be considered a pseudo-prequel?). Of the top twenty grossing films of the last year, only two were original and not based on a previous work (Us and Once Upon a Time …in Hollywood). Two of these exceptions also happen to have the lowest budgets of any of the films in the top twenty. Us has an estimated budget of $20 million, and Joker has an estimated budget of $55-77 million. Looking at previous years over the last decade, you will find a similar trend – the more original the film, the lower its budget tends to be.

But, more importantly is the fact that in today’s film industry, you have to spend a lot of money in order to make a lot of money. While low budget films are more accessible than ever these days, they rarely make much of an impact at the box office. Mid-priced films also don’t have the draw that they used to. Unless it is an Oscar-hopeful (with attached high-caliber star-power), or related to a very popular existing franchise, the mid-priced film doesn’t make a whole lot of sense in today’s film industry (especially when you look at the types of profits being raked in by big-budget films, see below). Over the last few years there have been many prominent figures in the industry who have lamented on the decline of the mid-priced film.

Without the pandemic, I believe we would have seen even further decline of the mid-priced film over the next decade. Even Oscar-hopeful films, which had previously been some of the most profitable lower-budget films released every year have budgets that are ballooning into blockbuster territory (1917’s budget was $100 million, The Irishman was budgeted at $159-250 million!). For movie studios, it makes sense for them to invest in prestige pictures. Although we can’t really determine the earnings of The Irishman, we know the Oscar buzz and attention it earned did wonders for bringing attention to Netflix and highlighting the potential quality of its original films. But the point remains the same – to have an impactful film, studios must spend more than ever.

But with the impact of the pandemic, that could change. As I detailed last week, if the film industry wants to maintain its profit margins in an era where the market could conceivably shrink, it will need to consider two changes to its current approach. The first change would be to appeal to a broader audience, specifically an international one. With the decline of the domestic box office, Hollywood will need to look at what changes they can make to the content of a film in order to draw in a more culturally diverse audience. The second, and more straightforward change is to simply make less expensive films.

Both of these changes will not be easy for an industry which has grown fat and happy doing the same thing over and over again. While we have already seen some efforts at trying to make big-budget films more appealing to non-domestic markets, the results have not yet been very promising. Look at the live-action remake of Mulan where Disney made a concerted effort to appeal to Chinese audiences. However, the controversial cast and several production decisions (including a lack of diversity among the creative team), ended up turning away part of the film’s domestic audience. Even if the film’s economic outlook was reduced thanks to the pandemic, it still showcased the complexity of trying to appeal to two different cultures at the same time. It will take some time for Hollywood to figure out the right way to make these types of films.

But simply lowering budgets will not be any easier. The cost to make a film has increased significantly over the last 20-30 years. In 1990, the most expensive movie of the year was Die Hard 2, which cost an estimated $70 million. 1994 saw the first movie budget cross the $100 million mark, True Lies. 1997’s Titanic was the first to cross $200 million, and 2011’s Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides was the first film with a budget estimated at more than $300 million (these are all unadjusted numbers).

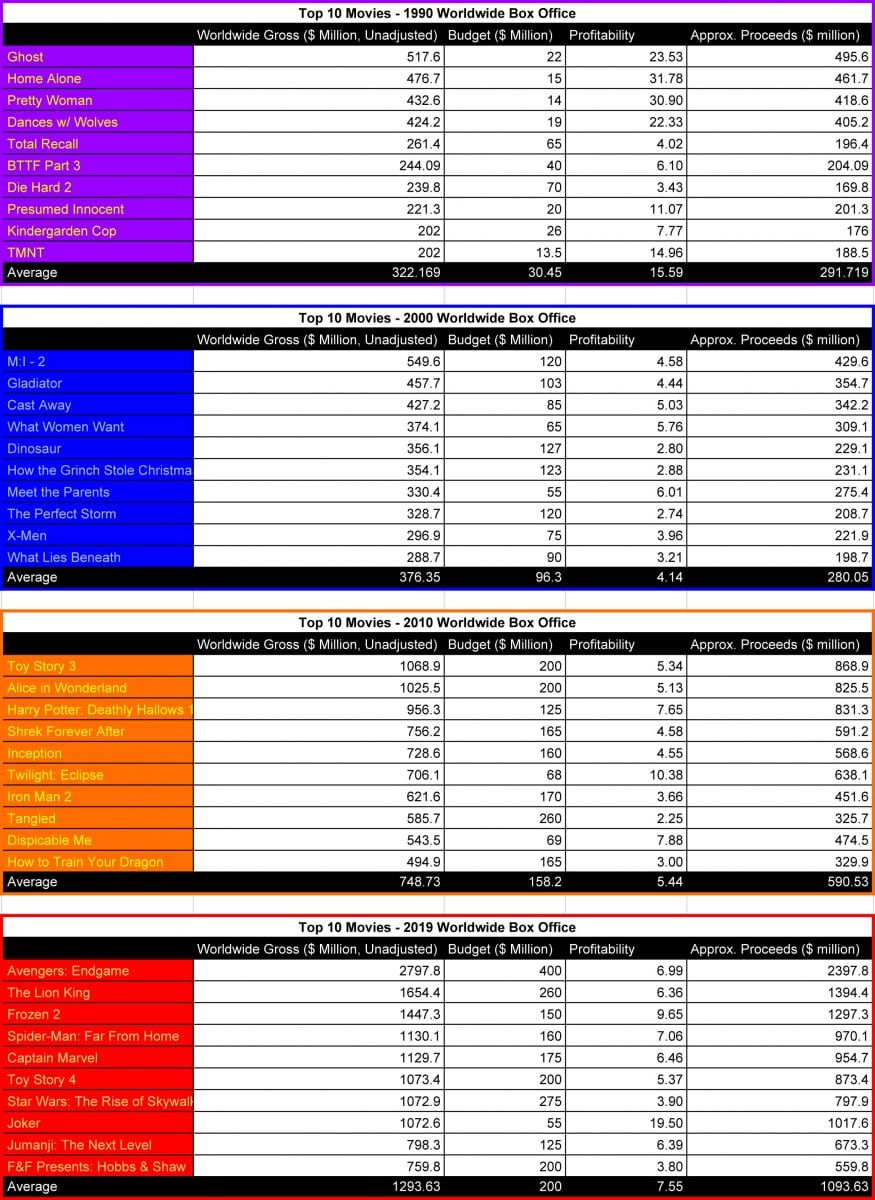

Below is a comparison of the worldwide box office proceeds of the top 10 films from 1990, 2000, 2010, amd 2019. For each film I have shown the estimated budget, and the profitability is how many times the film made back its budget. These numbers are unadjusted, but even if we did adjust them for inflation, the trends would remain the same. By looking at these numbers, we can see how major Hollywood films have trended when comparing how much they cost to how much they made.

As we can see, in 1990 there were a number of films which would be considered a surprise success. These were moderately-budgeted films which found considerable success at the box office. But a decade later, these mid-budget films have almost all disappeared off of the top ten. Average budget for a film more than tripled(!) yet the box office proceeds only rose about 17%. Ten years later in 2010, the average box office proceeds doubled, while budgets also increased, but at a lower rate (about 40%). In 2019, box office proceeds increased just less than 60%, while budgets increased 20%. Overall, movies are as expensive as ever to make, but they have been making more money than ever before. The industry is NOT as profitable as it had been in the past, but it was more profitable heading into 2020 than it had been in the preceding quarter century.

But this data, especially the 2019 data, does not really tell the whole picture. Advances in technology HAVE made many aspects of production easier (and therefore less expensive). This can be seen in how the budget increase for 2019 was not as high as compared with the increases we see over previous 10 year periods. In fact, when you take into account inflation, the average budgets of these top-10 grossing films in 2019 is only 6% higher than those in 2010! But if you think about it, there is no way that an expensive movie made today should only be 6% more expensive than back in 2010.

For instance, the complete lack of (big budget) original films these days means that all of them are based on some sort of existing property. That means studios have to spend a lot of time and money buying the rights to those properties and managing them. Development of a film therefore is much more complicated than it has ever been. Similarly, on the back end advertising is much more expensive than ever. Big movies can’t just put a trailer up on TV anymore. It requires a huge campaign to get people’s attention, and those services are often as much or more than the cost of making the film itself. We don’t know how much money a studio spends on a blockbuster film for rights management and advertising, but figure that you need to add at LEAST $100 million to the budget, if not more.

Because of the popularity of major film franchises, and the effort it requires to stay afloat on the ocean of advertising we are exposed to on a daily basis, studios aren’t going to significantly reduce their spending to maintain their presence in those areas. Disney will still want to make Star Wars and MCU movies. Warner Brothers will still make Harry Potter and DC movies. But they will have to find a way to reduce the cost of production of those properties.

Will that mean a reduction in star-value? A reduction in production values? Smaller scale films? More or less practical special effects?

Some of these changes are more feasible than others. For instance, franchises with already-established characters will want to have continuity of actors portraying those characters. Since those actors tend to be A-list stars, they won’t be cheap. As we’ve seen in films like Avengers: Endgame, killing off major characters isn’t just a decision to benefit the story, it can also be a decision to benefit the studio’s bottom line if said character is portrayed by one of the highest-grossing actors of this generation. Similarly, replacing actors portraying certain characters can also be a feasible way to lower costs, rather than killing them off. Look at the upcoming Batman film, the end of Daniel Craig’s run as James Bond, or how Solo: A Star Wars Story recast major characters in order to portray them as younger.

In this regard, franchises like Star Wars and James Bond (or even Star Trek and X-Men) are actually set up well for reducing costs in the future. With the end of the Skywalker saga, Disney does not necessarily have to worry about bringing back expensive actors to tell more Star Wars stories. And so, breaking from existing storylines is a way to potentially make less expensive films. Studios can make new films in established franchises which are NOT direct sequels. Just look at Joker. This is a film inside an established property, but its approach was much different than anything in the superhero/comic book sub genre we had ever seen before. Audiences were still attracted to the film because of the franchise, even if the outcome of this film was much different than the DC films which had come before it.

A-list celebrities are important for big budget films because they create interest and because they can help to create high expectations. But they aren’t the only ones who can help ensure the financial success of a film. More often than not, having an experienced director, cinematographer, writer, and producer is just as important. People at the top of the industry in these fields don’t come cheap though. They may find themselves in as much demand as the stars who are featured in their films.

So certainly, in addition to finding new actors to fill familiar roles in films, studios may also look towards less experienced filmmakers in creative roles. In many ways, the major franchises have already done this. Look at Taika Waititi’s experience with Thor: Ragnarok, or Patty Jenkins’ success with Wonder Woman. These are examples of filmmakers who were brought into the franchise fold after working on smaller budget independent films. Hollywood has done this many times before, and frankly they don’t always work out so well (consider Alex Kurtzman’s The Mummy). Part of the success of a film is how well the director is supported. So in many cases where a newer director was given the helm of a major motion picture for the first time, they may have struggled because the support from the other creative positions was not as strong as it could be.

Still, seeing new faces in directors chairs and new names in the credits of a film may be an increasing trend. Also consider the fact that after a filmmaker establishes a certain amount of success, they earn the right to dictate the types of projects they want to work on. So, in those cases the more experienced filmmakers who would otherwise command a high salary may want to work on less expensive, less demanding productions anyway. So, in this way, the success of tentpole franchises kind of automatically generates a certain turnover in those skilled areas. Otherwise, those filmmakers who really want to work on a franchise film must realize they have to give up some of their creative control and salary along with it, for the opportunity to be hired.

The exception is streaming services like Netflix, Amazon, or Apple who have a lot of capital and are willing to pay for major filmmakers to make films on their platforms. We’ve already seen David Fincher sign an exclusive agreement with Netflix for the next four years. This type of an agreement is beneficial to both parties. Fincher gets the creative control he desires and the budget necessary to see his ideas come to fruition, while Netflix gets to control the distribution of his work which will certainly be sought after by mainstream audiences. We’ve already seen Netflix release big-budgeted films full of A-list names in the cast, and if this makes business sense for them in the long term, I don’t know why they wouldn’t continue to make more films this way. After all, Netflix doesn’t have to worry about the traditional box office. I would expect more major filmmakers and stars to follow in David Fincher’s footsteps.

But more than just the type of film or the people who are making the film, what could change is the content of the film. Certainly, making a shorter movie can be more cost effective. A shorter run time would mean a scale back on action sequences, the size of the cast, the requirement for special effects, and simplified stories. Within the next few years I don’t think we will see another film with a scale as large as something like Avengers: Endgame. In fact, crossover films altogether may not be as common as they were over the past decade.

In terms of special effects, there are many new technological developments which will help to reduce the cost of making a film. “Stagecraft”, for example, is something that has been developed by ILM to allow filming in virtual spaces in real time. It uses projections and customizable lighting on a flexible sound stage to create virtually any environment imaginable. The technology was developed while making The Lion King and is being utilized during production of The Mandalorian. This type of technology eliminates the need to film on location, and can make reshoots much easier than before.

I would also expect there to be less reliance on CGI. The cost of Scorsese’s The Irishman famously ballooned because of the director’s insistence on using CGI to de-age his cast throughout the film. Traditionally Hollywood had used different actors or makeup to accomplish similar looks. I think part of the reason Hollywood has relied on CGI so heavily is because the scope of their films has expanded so much. Each film tries to outdo the last one, and so everything from the set pieces to the explosions gets bigger and bigger. We may see a scale-back of that tendency in the short term.

Like any other business, movies will only continue to get more expensive as long as there is a market to support them. With the box office numbers I’ve shown above, it is clear that Hollywood has found a pathway to more profit than ever over the last decade. Major franchises are very expensive to maintain, but the payoffs are huge because of their appeal which crosses boundaries of gender, age, and geography. Where as a film in the past would make the equivalent of half a billion dollars in profit maybe once or twice a decade, movies over the last decade began making a billion dollars in profit more than once a YEAR. And now with the pandemic studios suddenly have a year where they don’t have that type of money streaming in. There will certainly be consequences on the industry, it’s just a matter of how severe.

For more thoughts on the impact of the pandemic on the film industry, check out:

Study Abroad: How the Pandemic Has Accelerated a Shift in the Film Industry