Drive My Car is the latest foreign film to be nominated for Best Picture. Despite a lengthy runtime it more than deserves its place among the best films of the year.

The loss of someone close to you can be a very difficult thing to overcome. This is especially true when your feelings towards that person are unresolved. Movies often make the emotional play of trying to honor the person that is gone, but how can you do that if you are uncertain how you felt towards them? It is a much more complicated, and delicate situation of which there are no easy answers.

This is the dilemma that motivates Drive My Car. It is a beautiful, almost poetic look at the impact of unresolved loss. It explores the implications of never being able to find closure over the unexpected death of a family member, and how difficult it is to move forward in the face of those complicated emotions. But in addition to the topic of loss, the film brings forward a powerful discussion on the topic of communication.

Drive My Car

Directed By: Ryusuke HamaguchiWritten By: Ryusuke Hamaguchi,, Takamasa Oe

Starring: Hidetoshi Nishijima, Tōko Miura, Masaki Okada, Reika Kirishima

Release Date: August 20, 2021

Yūsuke Kafuku is a veteran actor and director, and is married to a screenwriter named Oto. Yūsuke finds out that his wife is cheating on him, yet decides not to discuss it for fear of changing their relationship. Unfortunately he never gets the opportunity as she unexpectedly passes away. Years later while working on a stage production, Yūsuke chooses to hire a man who was having relations with his wife in the hopes of finding out why she cheated on him. At the same time he meets a chauffeur who has also experienced an unresolved loss, and together they find a way to repair their lives the best they can and try to move on.

Yūsuke’s relationship with Oto is a complicated one. The loss of their young daughter decades ago has caused them both emotional stress, and they regret not having another child. They rarely speak or convey emotions mutually. However, they have a very intense physical attraction to each other, which is part of what keeps them together. As a screenwriter, Oto is only able to create her stories during sex, but she is unable to remember them, and so she relies on Yūsuke.

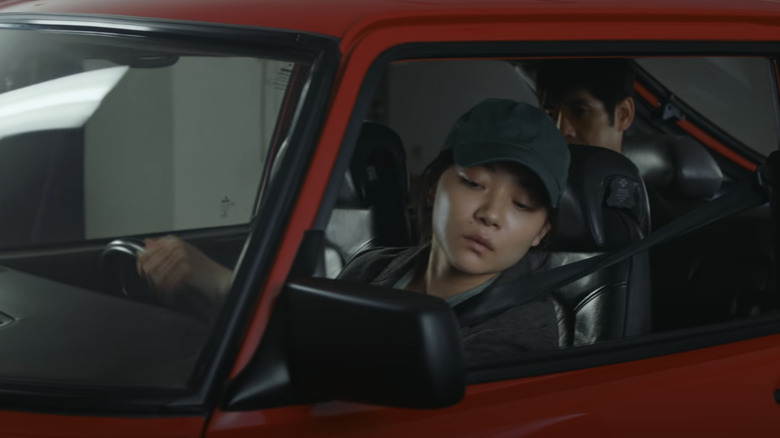

Oto gives Yūsuke purpose, and allows him to feel something real. The rest of his life is devoted towards his performances. He listens to Oto’s tape recordings of the plays he is performing in order to learn his lines and understand the cadence. Even when she is gone he can’t help but continue to listen to the tapes when he is driving his car. The tapes essentially keep her voice alive, and in essence she is telling him a story just like the connections they had when they were being intimate.

It is one of many brilliant, if subtle storytelling techniques the film utilizes. The play that Oto is reading on the tape is Checkov’s Uncle Vanya which happens to be the same play Yūsuke is directing two years later when he runs into his wife’s former lover. But the connections run deeper than the fact that Yūsuke is having to relive the same play over and over like something out of a twisted Groundhog Day. The film uses the dialogue from the tapes to convey meaning to events that are occurring in the film at the time that Yūsuke is listening to them.

This is almost like the film has a series of footnotes to convey as the story unfolds. Another is one of the stories that Oto tells Yūsuke at the beginning of the film, and is revisited as the plot moves forward. The story offers insight into Oto’s behavior, but more importantly it provides an uneasy connection between Yūsuke and the man who had relations with Oto, Kōji Takatsuki. Kōji is a famous actor with an anger management problem. He looks up to both Oto and Yūsuke, but will never be able to have what they have.

Another fascinating way the film handles the topic of communication is through the play that Yūsuke is directing. The production is multilingual, with each actor who doesn’t speak Japanese performing their lines in their native tongue, including one actress who performs in sign language. Through her work, Yūsuke gets to see the language of the play rather than hear it through the voice of his deceased wife via his tapes.

In a way this helps to break down some of the barriers he had with the material, and see it in a new way. Until now he had only associated his wife’s voice with the dialogue. It ran over and over in his head, but it prevented him from truly comprehending it because he was preoccupied with her death. In essence it was keeping him from letting her go. By seeing the emotion of the play in sign language, he comes to realize the need to move on.

There are more details encountered along the way which I won’t discuss here, but they all represent how impressively layered the plot is. Each little wrinkle feels like an additional messy compilation, but over time the film massages them all to fit perfectly together. What results is a beautiful prismatic structure where each moment and meaning can be seen refracted and reflected in another. All of this adds up to a very profound and moving film full of fascinating moments to contemplate upon.

I also appreciated the way the film paces itself, even if it takes a while to get where it’s going. It meticulously builds upon itself at a natural, if lumbering pace. This does result in a very lengthy film, but it is very much worth the wait. Furthermore, the film is full of these interesting traveling interludes which allow the material to breath and the audience to contemplate. It makes everything feel more natural to mimic the cadence of everyday life.

The repetition, the loneliness, and the isolation also help to reinforce the feelings of the characters and the themes of the film. The cast is very adept and punctual, without anything being too high or too low. This helps to reinforce the flow, but also allows the audience to not focus too squarely on one character or one strand of the plot. The film works best when you consider everything taken together, and you need time to properly come to appreciate it.

Drive My Car feels artfully bespoke, like the modern interpretation of the classic Russian literature its protagonist obsesses over. At first glance it might not seem like anything out of the ordinary, but the more time you spend with it the more you realize how every part is obsessed over and perfected to do its job. All of those fine details work in beautiful harmony to create a film that is as deep as it is compelling. Death may be a common topic in dramatic cinema, but few have been able to access the type of understanding and connection achieved here.