Our resident lover of horror games Becky got to speak with the composer of Still Wakes the Deep.

Earlier this month I had the opportunity to speak with composer Jason Graves about his work on Still Wakes the Deep, the latest horror game from The Chinese Room. Still Wakes the Deep was released on June 18, 2024 for Playstation 5, Xbox Series X/S and Windows.

Graves has composed for a number of video games over the years, but he might be best known as the composer behind the Dead Space trilogy and Supermassive’s The Dark Pictures Anthology. I previously spoke with him about his work on the most recent entry in that series, The Devil in Me.

I hope you enjoy this conversation about Still Wakes the Deep!

When this game was presented to you with its premise, what did you think about it?

I knew it was a horror game from the beginning, and I was wondering what they were going to do. Have you played any of the other Chinese Room games?

I don’t think so.

So they started with a horror game, called Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs. It was a pretty out there, scary game. But after that, they’ve done a lot of walking sim games. So it’s more of the experience of living in the world and exploring and doing things like you do at the oil rig, except there’s not a monster chasing you, and it was very immersive.

I was expecting the game to be immersive but scary, but then they kept talking about these Lovecraftian influences, and at the time, think it was basically a year before the game came out, I was brought on board, but there was not a lot of concept art, and the concept art for the entities in the game was there, but still being tuned. So I had ideas of what they were going to do, and they had ideas as well, but no one was really for sure how it would end. And there was a lot of back and forth, just creatively speaking, which naturally happens, about how long the ending would be and what the ending would mean and what the music needed to do.

But the one thing that they said from the very beginning was that they wanted music that wasn’t just scary. That means that they are going to try to find that cool Chinese Room, balance between not just scaring you all the time, but also making you invest emotionally in the characters and in the player that you are in the game. And they wanted the ending to be a big music moment with some dialog playing and a minute or two of just this otherworldly, ethereal something, and they explained how conceptually they wanted it to loop back to the main menu with the open sea and the ocean and general spiritual ideas, which I thought was cool.

Knowing all that, how do you make an oil rig in the middle of the ocean sound like the most terrifying place on Earth?

I think that’s something that goes back to 2006 when I started working on the first Dead Space game, and we were trying to figure out how to make things scary, because that was really the only order from the audio director [Daan Hendriks], was they wanted the music especially to be the scariest music ever written, right? Well, contextually speaking, a lot of different kinds of music could be scary, but I learned from the audio director back then that the real key to good scares, besides the obvious, the audio and the visuals need to be immersive, and you need to feel like you’re really there and you’re not thinking about other things in your room or in your house. You’re really into the game, but the suspension, the tension that happens before a creature makes a noise, or something jumps out and scares you, the tension is really the key to making people feel fear.

I think people who love being scared, they love that tension, because it’s like a tension, and then there’s a red herring or a big jump scare, and everyone screams, and then everyone laughs, because it’s this buildup of tension, and then you get scared, and it’s like a resolution and a relief. People laugh physically because it’s a hit of dopamine, because it’s a stress relief, and musically, a lot of times it’s just about holding and ratcheting up that feeling of anxiety that you get. So the music is always making you second guess what’s happening in the case of both games, [Dead Space and Still Wakes the Deep].

Like, for Still Wakes the Deep is that one of those creature things knocking around inside the oil rig? Or is that music? I can’t really tell. And then I have a sculpture that I commissioned from a friend of mine, which is all the crazy metal sounds that you hear in the score. The audio director said, “Let’s blur music and sound design.” So the sound design is already creepy, but if the music does more of the same, it’ll seem even less human and like more abstract and Lovecraftian scary. So we just embraced it. We pushed it as far as we could, and then more.

With the line being blurred between sound design and music, how do all the jump scares in the game work? Is it done differently than other games of that type

I would say from a music perspective, every game, especially horror games need to have these jump scares. It’s everything all messed up at once. But every game, every scary game that I do, there’s always a different opportunity to take the music and hook it into a part of gameplay, because it’s all based on the gameplay, and get it to trigger something interesting. Or different. And I’d say that this game in particular, I probably used all of my feathers in my cap of implementation that I figured out over the last 15 years since the first Dead Space. So a lot of it is talking with the audio team and figuring out how the gameplay works.

I think it’s scarier because it’s a survival game, and you can’t defend yourself. Your only choice is to either hide or try to run away. And some of the encounters just amplify that. There’s a lot of interactions with the main monsters in the game that are 8 to 12 minutes long as you’re playing and making decisions, but the music itself is probably broken up into at least 10 or 15 separate chunks. Then those individual chunks have lots of layers that can be turned on or turned up, depending on what’s going on with the gameplay. So if you hide, a lot of those layers will turn down, and you end up hearing something that’s just very tense and sort of moving, and your focus is drawn towards the sound design of the creature screaming at you and rumbling around and making all these crazy noises.

And as you start to move, the music comes back up, but it’ll be different, because now you’ve gone through a doorway that has triggered a different part of the music. Things are also time based. So if you sit still for 60 seconds, the music’s not going to sit there and play the same thing every 15 seconds in loop. It’s living, breathing, lots of things constantly being turned up and down, completely based on your gameplay, which makes it that much scarier.

That’s another thing I was going to ask because, everyone’s going to play it differently, and I was wondering how you would account for that, because no two players are going to do it the same way.

It’s like, if you picture a symphony orchestra, which we did not use for this game, but if you picture a symphony orchestra, instead of playing through the whole thing of Beethoven, it’s recorded. So just some of the high instruments play, and then some of the low instruments play, and then the drums play, and all that gets recorded separately.

So in that sense, my job is kind of finished, because what we’re doing is we’re hooking those individual sections up to the game, and the game is determining when the drums play versus when the strings play, versus when it plays something else, and it all is literally based on the player’s movement. The player is the conductor in front of the orchestra, kind of cueing each section to do different things based on gameplay. They just don’t know that they’re doing it, because it’s all working behind the scenes.

So we the player are determining the experience we get.

The idea would be, let’s say you watch a horror film. In the movie, this character is really scared, and they’re looking at the front door, but they’re hiding under a bed. They’re like, I want to run out of the front door. It’s open. I can get away. They sit there and look around for 10 seconds, and then they sprint for the door, and the killer jumps out at the last second, and there’s a jump scare in a fight. Well, that always happens the exact same way. And the music is highlighting when the person sitting there, and then when they start thinking, and it builds up a little bit before they start to run.

So the game music would do the exact same thing, except if you’re playing that version as a game, instead of [sitting] for 10 seconds, you could just run immediately, or you could sit there for 30 seconds. So the game is constantly listening, watching what you’re doing, and pulling all that music and turning up the appropriate music. I have said, as soon as you hit run, it’s going to take the player two seconds to scramble and start running. So I’m going to write a two second crescendo that makes you panic even more when you start to run. But that only gets triggered right before you hit the button, and the Chinese Room [will] say, “Okay, we’re actually going to make it when you hit the run button, it makes you scramble, and you slip, and then you get up, and it takes five seconds for you to actually start running.” So then I would write a piece of music that accentuates that for five seconds.

The Rig that you built specifically for the game. How did all that come about?

Well, first of all, I’m a percussionist and a drummer, so for me, I was literally just using this little Chinese bell and this little tiny finger cymbal, and rubbing them together and just doing different things to get some sounds. That’s very par for the course for me, and the way I think about textures and rhythms. So the audio director, Daan Hendriks, was the one that originally said, “Hey, why don’t you order something online?” He had a couple of online examples, because people make things on Etsy and stuff that you can hit and bow. And you don’t need to be a classically trained percussionist. You just smack it and it makes noises.

And I didn’t really know what he was talking about, but as soon as I clicked on the first link, I said, “Oh, better than that. I know exactly what we need to do. We need to hire my friend Matt [McConnell] to build something bespoke, like specific to what this is.” You know, these things are great, but I’ve already seen these in other games, like Alan Wake 2 and a couple of other games. I know they bought that thing, and another person bought that same thing, and that’s great, but the last thing I want to do is buy the same thing and use it the same way.

Matt [McConnell] built something for me for Tomb Raider and I hadn’t worked with them since then. So I contacted Matt [McConnell]. He was totally on board, and did the whole thing in three weeks. And since we had worked on Tomb Raider before, he understood that I needed to have lots of things like spikes to bow and metal plates to hit, and lots of resonance and things like that. And he built it with that in mind. Then I just took it back to the studio and started recording with my microphones and using the computer. It was one of those, I don’t know if this is going to work. I have no idea what it’s going to sound like. And then the more I mess with it, the crazier sounds I could find, and that’s what you end up hearing on the score. About half of it is me playing it in real time, but the other half is manipulated in the computer.

What would normally be like a high whale cry or dolphin squeak ends up sounding like this huge screeching banshee from hell that’s 50 feet tall, and it’s all coming from that sculpture, because it has all that resonance and all that metal. And that was the score from the beginning, I wanted that to be half the score. And while I was waiting for Matt [McConnell] to make that, I was experimenting with some of the live musicians, but I didn’t really write anything until he gave me the final sculpture. So I just started recording and writing immediately. It was direct inspiration. The score literally wouldn’t sound the same if I had some other metal thing that somebody else had built.

Was it coincidence or intentional that it resembled an oil rig

That was Matt’s doing and completely intentional. I know it’s so cool, but it makes sense. Like, as an artist myself, I would understand. I told him, conceptually, it doesn’t need to look like anything, you build whatever shape you think is going to work. I went out to his place once and tried a couple of prototypes, and he made all that metal himself. He was rolling the metal and everything was handmade, because that’s what he does. He is literally a metalsmith. So he was trying different thicknesses of metal and different widths of the bars and the lengths, just lots of experiments. That was all him. He’s a super creative, gifted guy.

For the creatures, I’m assuming, plural creatures that have taken over the rig. For those, how did you work with them musically?

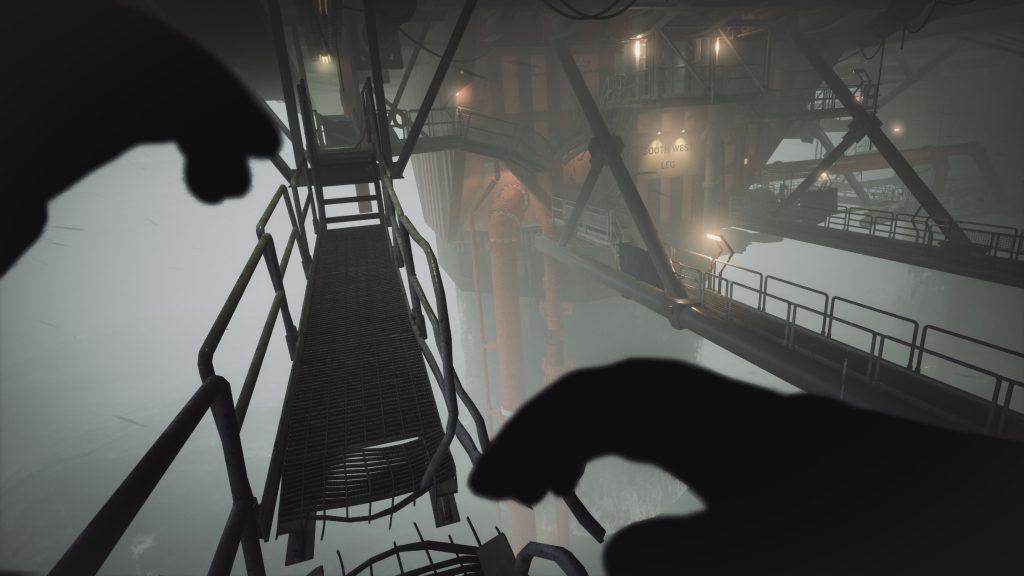

Yeah, it’s very Chinese Room, because [of] the general concept of the game. I don’t think this really gives anything away for you or for anyone else that’s seen a trailer; you’re on this oil rig in the 70s. You’re isolated, but you’re isolated with all these coworkers that you are personally friends with. No stone was left unturned, it’s a very immersive setting.

These are your friends, your comrades. You’ve been working with them for a long time. However, from the very beginning of the game, you’re just trying to leave. You show up, and your boss is like, “Get off. You’re out of here. You’re fired, you’re gone. Take a hike.” That’s the beginning of the game. No spoilers there. However, being an oil rig, it has somehow driven its spike into something in the ocean and pierced it, and this thing is reacting and defending itself.

So you’ve got this Lovecraftian, cosmic, mental weirdness that happens, but also physical transformations of all of these people that were once your crew. Some of them are really sad because no one is trying to get you the way monsters always are in most games and in all the movies, they don’t even understand what’s going on. And what I love about it is you’ll hear them speaking lines that you’ve had with them before, and they’re looping these lines because they’re stuck, and they’re like, “Wait, what? What’s going on?” Then they accidentally lash out and kill you.

It’s a gray area in terms of monster versus a person, which is why I like the idea that they didn’t make it “you have to kill the monster.” You need to get away. And even the voiceover for the main character will say, I’m so sorry. I have to go. So there’s a lot of empathy there, which doesn’t make it less scary, but I think makes it more emotionally telling and your question was, how do we score the monsters. My line of thinking here was, when you’re dealing with all the people and you’re having these conversations, especially the first act, until something happens there’s not any music. And a lot of times with most games, the beginning and the end of the game is what you finish at the very end of the development cycle, because those are the two most important parts. The beginning has to be really polished, and the end has to be satisfying.

Those are the hardest things to pull off from a technical standpoint, because you want to make sure that the game’s impressing at the beginning and at the end. So we left the beginning alone and didn’t do any music yet. And then as we were approaching the end of development time, Daan Hendriks said, Okay, well, what music should we do? You know, when you’re talking to this person and you’re talking to that person, and I was like, you don’t need any music. First of all, this is in the 70s, and in 70s horror films there’s no music until the killer strikes. It’s not like movies today where there’s music through the entire thing.

I wanted the music to mean something when it came in. So you get this super creepy [sound] when you’re dealing with these creatures on the oil rig. It’s this crazy, creepy rig sculpture sounds being bowed, with these woodwinds doing all these nasty, snarly, breathy, unhuman, unwound sound effects. That’s the scary creatures. When you’re actually dealing post-conflict with people talking about what happened, or talking about someone else, then we have music that is a string quartet, and it’s very tonal and melodic, and it’s the only time you hear the string quartet in the whole game.

Then we go 180 degrees, and that gets ripped out from under your feet, suddenly you’re in another encounter with a different creature, and you get all these crazy, menacing, abstract unnatural sounds, and you survive that, and then maybe there’s some silence, or you’re in the water, and it’s really floaty and kind of benign and comforting, but also apprehensive. Everything’s up in the air, and you don’t really know where your footing is, musically speaking, and then [there’s] another creature. It’s just that constant going back and forth.

Was there something specific for the main entity itself?

I didn’t write anything specifically for, I think it’s referred to as “the horror.” That’s the official term. I did this thing with some whistles as an experiment for the water, because I thought that they sort of sounded underwater when I used them in the computer and pitched them down. And they’re all pitch bendy and floaty, which is what you hear most of the time when you’re swimming in the water. And Dan really liked that texture, and latched on to it, and kept saying, well, let’s do something with those whistles here. Maybe here, we could have something with the whistles.

And at the end, there’s a couple of moments where the character just stops, and you lose control of the controller for a second. And you look over and you get the cinematic view from up high, or maybe from underneath the rig. There’s a couple of cool moments where you can see what it is in all of its glory. And Dan kept saying, let’s put the penny whistles there. Let’s put the penny whistles there. So whistles there. So the penny whistles and it’s this progression, just two minor chords very far apart from each other, going back and forth every 10 seconds, that became the theme or the the texture that was associated with this unknown entity in the depths of the ocean.

And so you said there weren’t many other instruments included besides the rig, um, you said there were some woodwinds and just the Quartet. so there was nothing else, non conventional, besides the rig.

No. I had this synthesizer, [it] does all the bass sounds in the game. Lots of like, you know, John Carpenter, The Thing, sort of like just 70s synth, pulsing sounds, but also really abstract, kind of screaming, sort of tension, sort of things. But that was really it. It was the sculpture, the low woodwinds and just this synthesizer playing one note at a time. That’s pretty much two thirds of the score. And the other third of the score is the string quartet, with the woodwinds playing a much more, tonal, pleasant sound, and the synthesizer very warm and comforting, playing the bottom. Then you can hear The Rig in the background, but it’s got a lot of reverb on it, and I tried to make it sound more like ocean waves, or like the water hitting the rig.

So it’s very blurry and splashy sounding, or some very gentle taps. So it’s just doing a very standard rhythmic thing. But I also love the idea that The Rig and the synthesizer and the woodwinds can be both sides of the same coin. They can be friendly with the string quartet and compassionate and empathetic. They can also turn on a dime, just like the game does, and get completely monstrous and abstract and terrifying. Because in reality, that’s what happens to the crew. They’re your friends, and they get contorted and twisted and ripped apart and put back together again by this entity, and I like the idea of the instruments being able to kind of mimic that path, if that makes sense.

My last question is, how did working on all this for Still Wakes the Deep differ or compare to other games you’ve worked on, like The Dark Pictures Anthology.

The great thing about games is every one of them has a completely different story, so that makes it easy for me to differentiate the palette, like what sounds that I want to use. And I think a lot of this goes back to me being a percussionist. If I’m playing, [let’s say a] triangle. In that example I was giving with the conductor in the Beethoven piece, I probably won’t play triangle the whole time. I’ll play triangle, and then I’ll put that down, and then I’ll go play cymbals, and then I might go play some snare drum, and then maybe some xylophone. I’m used to playing lots of different instruments myself.

So the first thing I usually do with any game, regardless of whether it’s scary or not, is, [discover] what instruments can I find to play or purchase that I’ve wanted to get to play that would work well with this game? In this case, it was that synthesizer, I bought that for the game, and then obviously I had Matt [McConnell] commissioned to build the sculpture for the game. I would say the sculpture is what makes it really different and unique.

But the limited number of instruments definitely sets it apart from some of the Dark Picture games, because they have a much more far reaching, broad concept. Sometimes they take place in different time periods hundreds of years apart. There’s a lot of things that we need to touch on [in those games], and the palette is much more broad as a result of that, except for Little Hope. Little Hope was very similar to Still Wakes the Deep in that it was a very small set of rustic, intentionally out of tune, bad sounding instruments.

But the sculpture, I think, is definitely what set the score [for Still Wakes the Deep] apart, because it literally defines the sound of the entire score. We’ve got this metal thing. It looks like an oil rig. You can make all these crazy, scary sounds on it, and the woodwinds sound scary, and the strings sound really pretty, and you only hear them during the more emotional moments. It’s nice and abstract and small, but it works together well.

I had no idea that was going to sound like that. It was all, until more than halfway through, basically me saying “This was a big mistake. What was I thinking? Why did I think that I could base an entire half of the score just on me playing the sculpture? I’m never going to be able to get all these different sounds” and then I end up spending a day, and it’s like, whoa. The first time I heard the sound [in the game], that’s just me bowing the sculpture, except it’s just pitched really low in the computer. And I hit the key on the computer when it did it, and I was like, “I found it.” That’s amazing that I’ve never heard anything like that. Then every time that I did it, I just do another bow, and it sounds completely different. It’s the sculpture. That’s the short answer.

……………………………………………………………………..

I would like to thank Jason Graves for once again taking the time to sit down and talk with me about his work on Still Wakes the Deep. The game is currently available for Playstation 5, Xbox Series X/S and Windows.